A simple model for growing a brain

23 Mar 2015Today I had a chance to read a paper by Song, Kennedy, and Wang about their model for explaining how brains are wired up at a high level (explaining how areas are connected, not the detailed wiring of neural circuits). It’s very simple, but manages to capture some complicated aspects of brain structure.

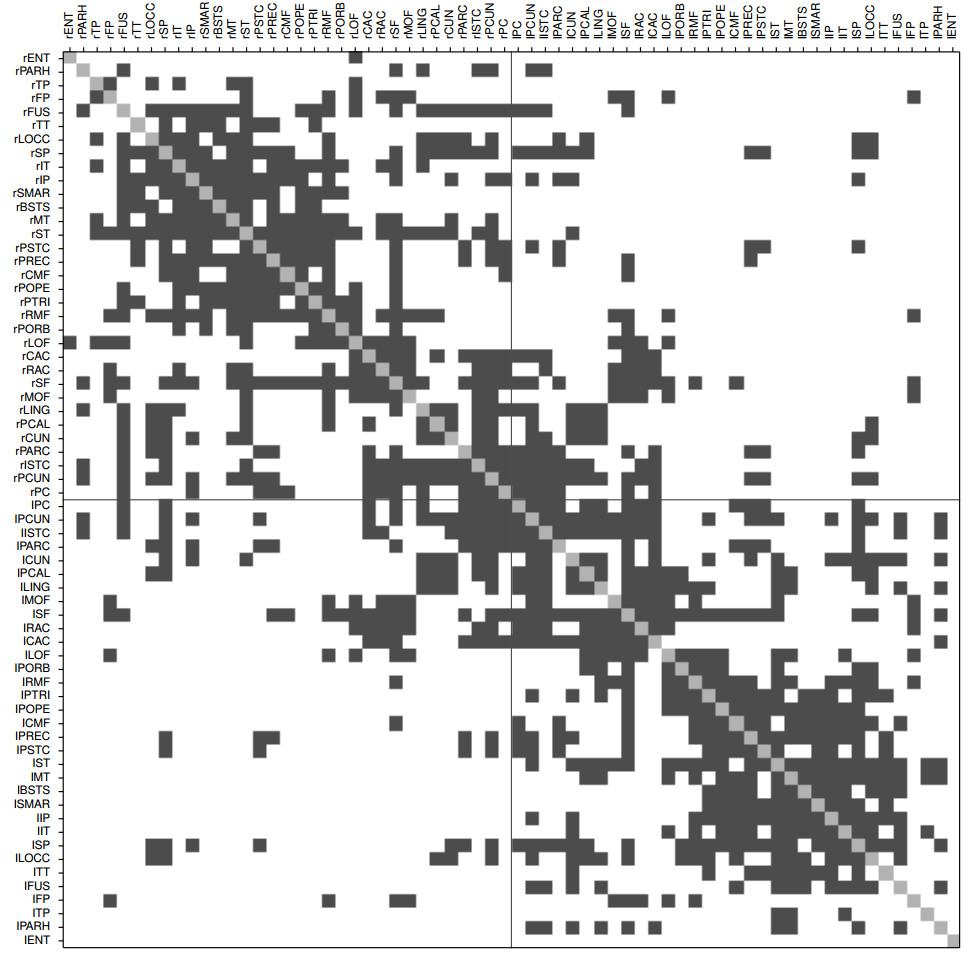

The goal of the model is to offer some explanation for area-to-area connection patterns across species (humans, monkeys, mice). For example, the human connection matrix looks like this (from their supplementary material):

Gray squares show pairs of regions that (we think) are connected to each other. This looks complicated, and it is - every region has a different connection pattern, some are similar to each other (neighboring rows), some are very dissimilar, some regions (rows) have lots of connections and others have few, etc. The Song et al. paper starts by discussing the features of these matrices that seem predictable and similar across species, but the part I found more exciting was their proposed model for how you would grow a brain with these properties.

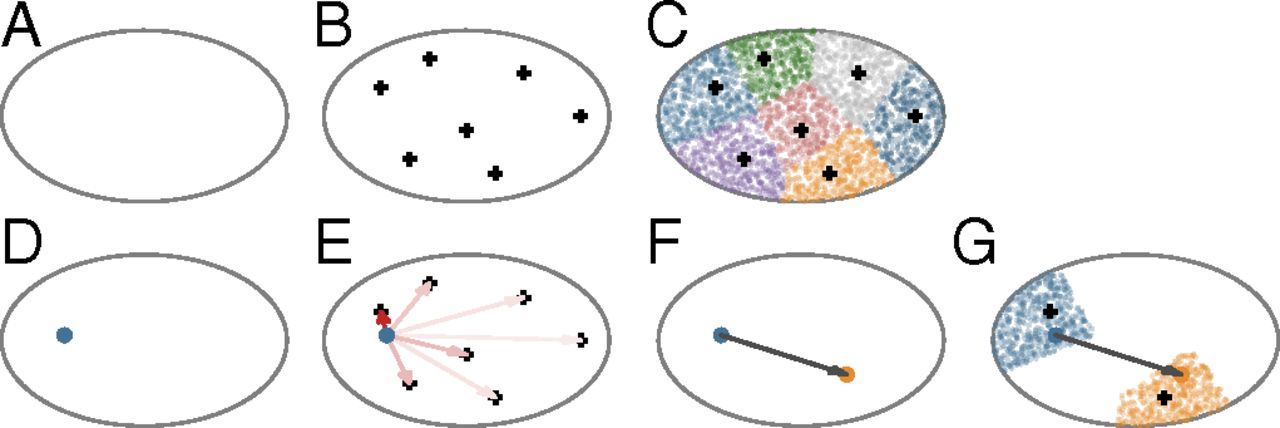

This figure from their paper shows the setup. You first randomly choose a bunch of points as the centers of brain regions and randomly create a bunch of neurons, assigning each neuron to belong to the closest region center (A-C). Then, to grow a connection out from a neuron, you pick a direction as a weighted average of the directions to all region centers (with closer regions weighted more heavily), and then grow in that direction a random amount (with short connections more likely than long connections) (D-G). That’s it! Every neuron grows without talking to any other neuron, and they are not even really aiming anywhere in particular.

This simple set of instructions is enough to produce some of the structures in real connectivity matrices, like relationships between how similar the connections are for two regions and how likely they are to be connected to one another. One of the take-aways is that spatial position is a very important feature for wiring brain regions - just adding a bias to connect close regions rather than distant regions is enough to explain a lot of the brain data. This sounds sort of obvious, but spatial position is often ignored in many analysis methods, and I’ve been recently proposing ways of incorporating spatial information for understanding connectivity at both the whole-brain and region level.

There is a lot missing from this paper - it makes a literal “spherical cow” assumption that the brain is a solid ellipse, assumes that neurons are fired in straight lines like a laser, and doesn’t account for how brain size changes during development. But in some ways it makes the result even more impressive, since they can explain a lot of the data without using any of these details.

Comments? Complaints? Contact me @ChrisBaldassano