Reality, now in extra chunky

02 Aug 2017Our brains receive a constant stream of information about the world through our senses. Often sci-fi depictions of mind-reading or memory implants depict our experiences and memories as being like a continuous, unbroken filmstrip.

From The Final Cut, 2004

From The Final Cut, 2004

But if I ask you to describe what has happened to you today, you will usually think in terms of events - snippets of experience that make sense as a single unit. Maybe you ate breakfast, and then brushed your teeth, and then got a phone call. You divide your life into these separate pieces, like how separate memory orbs get created in the movie Inside Out.

From Inside Out, 2015

From Inside Out, 2015

This grouping into events is an example of chunking, a common concept in cognitive psychology. It is much easier to put together parts into wholes and then think about only the wholes (like objects or events), rather than trying to keep track of all the parts separately. The idea that people automatically perform this kind of event chunking has been relatively well studied, but there are lots of things we don’t understand about how this happens in the brain. Do we directly create event-level chunks (spanning multiple minutes) or do we build up longer and longer chunks in different brain regions? Does this chunking happen within our perceptual systems, or are events constructed afterwards by some separate process? Are the chunks created during perception the same chunks that get stored into long-term memory?

I have a new paper out today that takes a first stab at these questions, thanks to the help of an all-star team of collaborators: Janice Chen, Asieh Zadbood (who also has a very cool and related preprint), Jonathan Pillow, Uri Hasson, and Ken Norman.

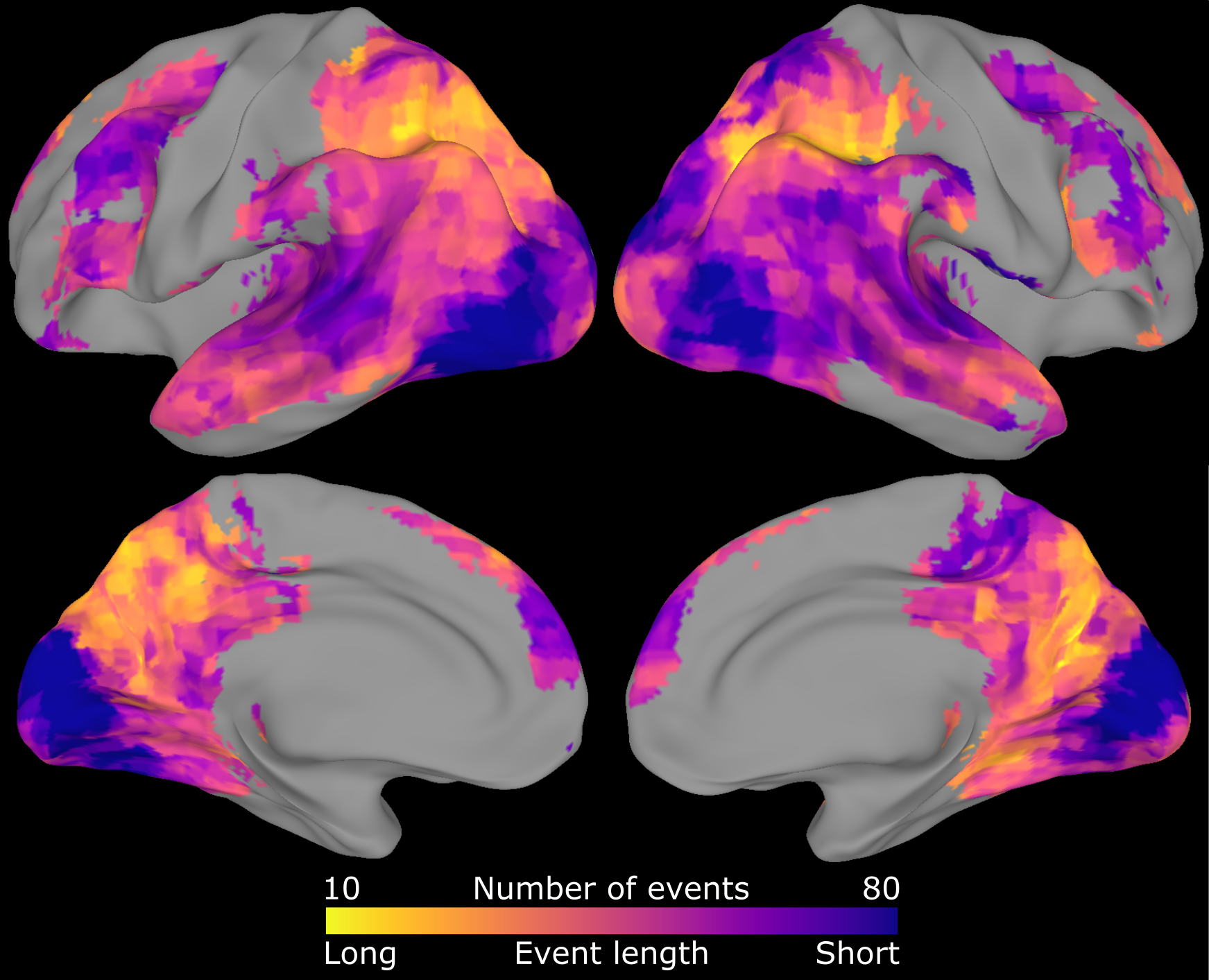

The basic idea is simple: if a brain region represents event chunks, then its activity should go through periods of stability (within events) punctuated by sudden shifts (at boundaries between events). I developed an analysis tool that is able to find this kind of structure in fMRI data, determining how many of these shifts happen and when then happen.

The first main result is that we see event chunking in lots of brain regions, and the length of the events seems to build up from short events (seconds or less) in early sensory regions to long events (minutes) in higher-level regions. This suggests that events are an instrinsic part of how we experience the world, and that events are constructed through multiple stages of a hierarchy.

The second main result is that right at the end of these high-level events, we see lots of activity in brain regions the store long-term memories, like the hippocampus. Based on some additional analyses, we argue that these activity spikes are related to storing these chunks so that we can remember them later. If this is true, then our memory system is less like a DVR that constantly records our life, and more like a library of individually-wrapped events.

There are many (many) other analyses in the paper, which explains why it took us about two years to put together in its entirety. One fun result at the end of the paper is that people who already know a story actually start their events a little earlier than people hearing a story for the first time. This means that if I read you a story in the scanner, I can actually make a guess about whether or not you’ve heard this story before by looking at your brain activity. This guessing will not be very accurate for an individual person, so I’m not ready to go into business with No Lie MRI just yet, but maybe in the near future we could have a scientific way to detect Netflix cheaters.

Comments? Complaints? Contact me @ChrisBaldassano